Falling towers

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal

-T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

In the wake of 9/11 there abounded a profusion of conspiracy theories, almost all of which were predicated on the assertion that the Bush administration were involved in, or had advance knowledge of, the attacks. One of the more outlandish claims was that no planes were involved in the attacks and that sophisticated holograms had been used to produce highly convincing 3-d simulations. Much of this incredulity stemmed from suspicions around the authenticity of the footage that was broadcast live on TV that day. For many, these moving images looked contrived and a little too much like a disaster film. The cinematic nature of the atrocities troubled veteran director Robert Altman who, in an interview given weeks after 9/11, argued that it was evident from the manner in which the attacks were choreographed that they had been inspired by Hollywood. He stated “movies set the pattern and these people have copied the movies. Nobody would have thought to commit an atrocity like that unless they'd seen it in a movie. I just believe we created this atmosphere and taught them how to do it.”

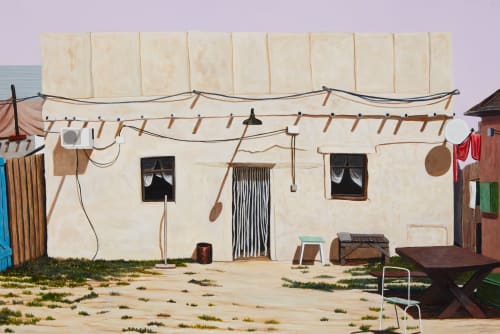

In the 20 years that have passed since 9/11 the boundaries between factual documentation and confected phantasmagoria have become increasingly blurred. The internet is now awash with persuasive deep fakes while HD footage of ‘real life’ events is often so vivid that it appears unbelievable. This is exemplified by the videos of Jeff Bezos’ notably phallic New Shepard rocket launching last April, many of which look like unconvincing CGI. An exploration of cinematic images and how they relate to reality is central to Stephen Loughman’s mode of conceptual painting. He trawls through the overabundance of popular film, sourcing scenes to translate into paint. ‘Hard news’ frequently influences what scenes Loughman choses, albeit tangentially. Take for example his painting of a collapsed rail viaduct lying at the bottom of a ravine. Plumes of smoke rise from this wreckage, indicating the carnage has just occurred. This vista is taken from Cassandra Crossing, the 1978 disaster film in which an outbreak of lab-cultivated plague breaks out amongst passengers on a train travelling between Geneva and Stockholm. Elsewhere in this exhibition is a tondo in which the aforementioned twin towers are depicted submerged under water. This is one of the more memorable scenes from Steven Spielberg’s A.I. (2001) set in an alternate future where biblical floods have consumed many cities.

While knowledge of Loughman’s sources is illuminating it is not a prerequisite for engaging with his work. The scenes that he isolates and paints can function outside of the filmic narratives of which they were originally a part. They are essentially primordial images and so their symbolism may be apprehended autonomously. The paintings in this exhibition depicting man-made infrastructures in states of ruin can be situated within a tradition of the Friedrichian sublime, they are ruminations on the futility of humankind and the inevitability of death. At heart of Loughman’s methodology is an investigation of the archetypal motifs that are omnipresent in all forms of mass media and entertainment. The resultant paintings are condensed expressions of arcane appetites and fears which although frequently concealed are ultimately irrepressible.

-Pádraic E. Moore, 2021